Slanted & disenchanted

Are we living in an age of cultural mesmerism?

TL;DR:

Uncertainty makes us anxious, and when we’re anxious, we’re more likely to trust people who seem most sure of themselves – even if they can’t back it up with evidence. But leadership built on charisma alone doesn’t hold for long. Symbolic power has to be grounded in something testable and real. Without that, trust collapses, and the systems we depend on begin to fail.

The challenge isn’t to deny our need to believe, but to ask whether what we’re believing in can stand up over time.

The assumptions that once grounded economic, political, and social life are breaking down.

In finance, meme coins are traded at high volumes despite having no underlying assets or utility.

In mental health care, therapy – a social healing practice centered around the relationship between two human beings – is increasingly delivered through AI-powered chatbots and scripted digital tools.

In the creator economy, complex subjects are compressed into soundbites and used mainly as a platform for the host’s personality.

And in national politics, long-standing boundaries between government branches are being squeezed, as disputes over presidential immunity and judicial enforcement take center stage.

Across all sectors, the fundamentals are being questioned, renegotiated, or bypassed altogether. The values and norms that have held institutions together are eroding, and a new cadre of charismatic figures are promising to deliver better systems and more “efficient” results. They speak with confidence and authority, positioning themselves as the ones who see meaning in the chaos and can envision what comes next.

But how do we know what – or whom – to believe?

Our founding fathers once asked a similar question.

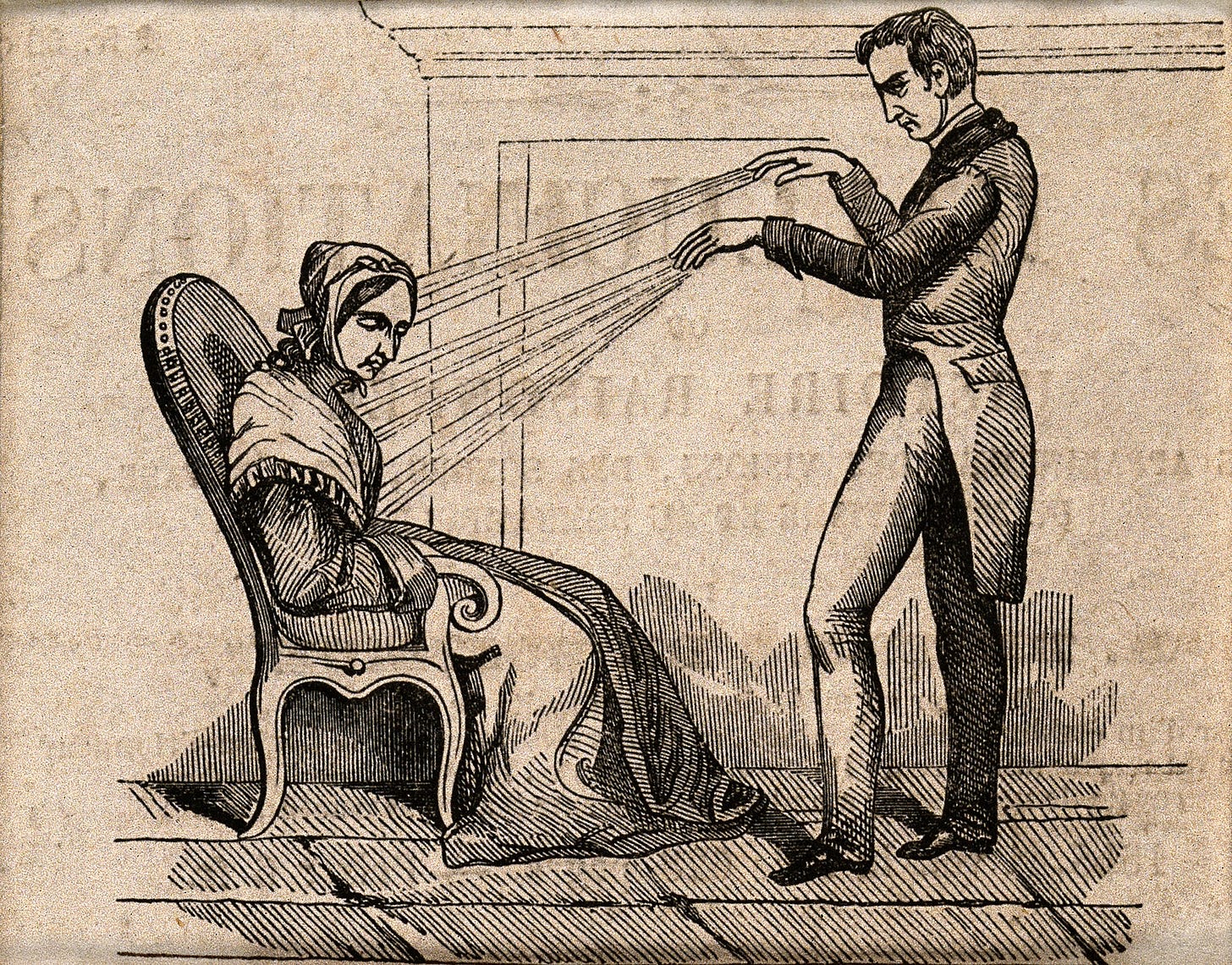

In 1784, Benjamin Franklin lead a French royal commission investigating Franz Mesmer, a physician who claimed to heal patients using an invisible force called "animal magnetism." Mesmer treated a range of ailments, often causing patients to weep, faint, or convulse while receiving his treatment. But the scientific basis of their improvement was unclear.

The commission conducted what would become the first placebo-controlled trial. Some subjects were blindfolded and told they were receiving Mesmer’s treatment. As usual, they began sweating, crying, even fainting. But when the same procedures were carried out without any mention of Mesmer, nothing happened.

The commissioners concluded it wasn’t Mesmer’s technique that produced results, but the patients’ expectations, the rituals surrounding the treatment, and most of all, their belief in Mesmer as a healer.

The problem wasn’t that Mesmer’s method didn’t work. It did, insofar as people reported feeling better. But the results weren’t generalizable because they depended entirely on his personality. His charismatic presence – not his method or theory – was the active ingredient. His power came not from evidence, but from the rapture his performance inspired.

Belief in Mesmer as a healing figure filled a void in people’s understanding of illness, but it also deprived the broader medical establishment of shared learning that could produce better outcomes for more patients. Only he could do it.

This same dynamic is reshaping public life now.

Across industries, authority is being renegotiated in real time. Economic value, institutional boundaries, and professional credibility are no longer anchored by shared standards. The best evidence often isn’t followed because most people don’t know what it is (including our elected leaders). The unwillingness to agree over the facts creates the illusion that the evidence is changing or that previous conclusions are no longer valid.

And in this vacuum, influence often flows not to those with the strongest knowledge base but to those who appear most sure of themselves. A kind of “cultural mesmerism” has taken hold, shaped by systems and figures that generate the appearance of truth – not through evidence, but through suggestion, performance, and confidence.

Three days before his second inauguration, Donald Trump released $TRUMP.

Promoted as "The Only Official Trump Meme," it appeared to extend a familiar American tradition of minting coins to commemorate presidential transitions and other historic milestones. These coins are symbolic by design, meant to express national pride or party affiliation rather than function as financial assets.

But $TRUMP disrupted that frame. It was explicitly intended to be traded as a speculative asset, and its value was grounded entirely in Trump’s personal brand. It’s meaning wasn’t rooted in national identity or institutional memory, but in personal allegiance to an individual. It offered supporters a way to identify with Trump and the vision he promoted, emotionally and financially.

In doing so, $TRUMP imitated the form of democratic ritual while hollowing out its useful civic function. What was once a collective artifact was reduced to a personal talisman.

The money is real. The mechanism is belief (not attention, as some mistakenly claim). And, as always, the one who stands to gain the most is the figure at its center.

These charismatic figures don’t only succeed simply because people are naïve or gullible. They succeed because people are anxious.

When institutional ground feels unstable – when trusted systems are slow to adapt or appear indifferent to everyday concerns – people look for something that makes sense, feels good, and instills hope that helps them move forward. In desperate times, the will to believe becomes stronger.

The performance of certainty offers a kind of social balm, soothing confusion and relieving the burden of not knowing. The confidence man – or platform, or trend – speaks directly to these emotional needs, offering coherence without too much complexity, reassurance without clear accountability, and conviction without evidence.

This is the opening Mesmer walked through. And it’s the same opportunity being exploited now by the current cast of confidence people: financial influencers who speak with passion about topics they barely understand; AI-driven therapy tools promising 24/7 connection (somehow forgetting that literally no actual relationship in real the world is available all the time), and political figures whose charisma far outpaces their competence.

These aren’t always scams. Sometimes real innovation is occurring. But when the structure is built purely on emotional persuasion and detached from facts, the power of an idea depends entirely on the suggestibility of the audience. And its durability crumbles when the belief fades, often leaving a host of new problems in its wake.

Freud saw this pattern clearly.

In Totem and Taboo (1913), he described how children, “still at the mercy of the overpowering impressions of the external world…behaved as though their thoughts and wishes were omnipotent."

Freud called this illusion of psychic control magical thinking: the belief that simply willing, wishing, or performing an action can materially affect reality. It also resurfaces in adulthood, especially during moments of uncertainty or anxiety. (And sports.)

When a charismatic leader’s message reflects their audience’s lived experience, it can inspire people to imagine a better future. But when confidence outpaces substance, it can seduce people into magical thinking. The vision may appear credible, but if it’s built on fantasy, people eventually wake up.

And when they do, the collapse isn’t just psychological. It’s institutional. Betrayal leaves people exposed, vulnerable, and angry. The short-term gains may seem worth it, but the deeper cost is harder to repair: by the time disillusionment sets in, the old system may be too hollowed out to return to, and nothing better has taken its place.

Magical thinking shields children from what they can’t yet understand. For us adults, it becomes a way to avoid what we’d rather not face.

But it doesn’t just distort reality. It weakens the systems and institutions built to manage it.

Collapse doesn’t usually happen all at once. Often, it’s the result of a widening gap between what’s promised and what’s delivered. When belief detaches from evidence, shared experience, or institutional checks, trust erodes and systems start to fail.

Belief itself isn’t the problem. The danger lies in what we come to believe in, and why. Performance is persuasive, especially when the ground feels unsteady, and we desperately need hope. But confidence without substance doesn’t hold for long. And real damage isn’t just psychological collapse; it’s the cynicism that follows.

Symbolic power is a crucial part of leadership, but it must be tied to something verifiable. That means building systems and institutions that don’t rely on personality to succeed. It means slowing down, examining what’s real, and holding onto it, no matter how appealing the illusion may seem.

Wanna buy a $JOAN coin?